Germany

November 29, 2011

Wenn Samen der Ackerschmalwand Arabidopsis thaliana reifen, schrumpfen ihre Zellkerne und das Chromatin kondensiert

Die Samen von Pflanzen sind ein besonders biologisches System: Sie ruhen mit einem deutlich reduzierten Stoffwechsel, womit sie harschen Umweltbedingungen lange Zeit widerstehen können. In reifenden Samen beläuft sich der Wassergehalt auf unter zehn Prozent. Forscher des Max-Planck-Instituts für Pflanzenzüchtungsforschung in Köln haben nun herausgefunden, dass das Erbgut kompakter wird und die Zellkerne der Samenzellen schrumpfen, wenn die Reifung der Samen beginnt. Dadurch schützen die Samen ihre Erbsubstanz wahrscheinlich vor Austrocknung.

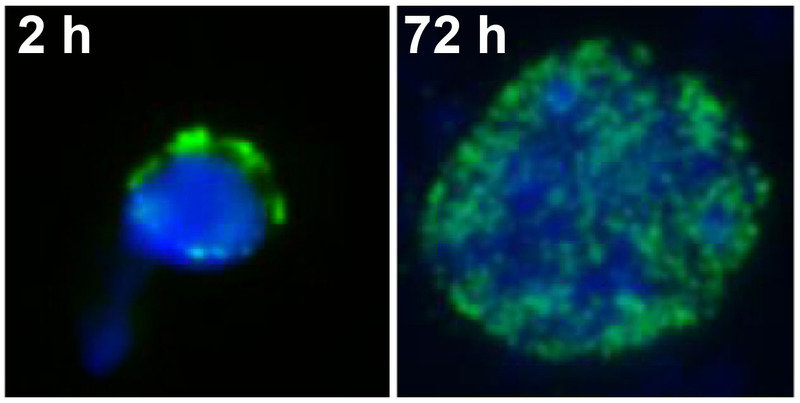

Kern eines Pflanzensamens im Ruhestadium (links) und nach dem Keimen (rechts). Im kleineren Kern ist die DNA (blau) dichter gepackt als im größeren Kern (grün: methylierte DNA). © MPI. Pflanzenzüchtungsforschung

Mit der Entwicklung von ruhenden Samen sind Pflanzen bestens auf wechselnde Umweltbedingungen vorbereitet. So können beispielsweise im Herbst gereifte Samen problemlos den harschen Bedingungen des Winters trotzen. Doch treffen die Samen im Frühjahr auf angenehme äußere Verhältnisse, keimen sie und fahren ihren mit halber Kraft laufenden Stoffwechsel wieder hoch. Bei archäologischen Ausgrabungen wurden sogar Samen gefunden, die einige Tausend Jahre überdauert haben und noch immer gedeihen konnten.

Trockene Samen sind ein Übergangsstadium zwischen Embryo und Keimling. In solchen Phasen müssen die das neue Stadium kontrollierenden Gene aktiviert werden, während Gene für das „alte“ Stadium stillgelegt werden. Die Gene im Zellkern sind von Proteinen umgeben. Dieser Komplex – das Chromatin – kann mehr oder weniger dicht gepackt sein. Der Grad der Kompaktheit reguliert die Aktivität der Gene: je „offener“ das Chromatin, desto besser die Gene abgelesen werden.

Ob der auf Sparflamme laufende Stoffwechsel oder der geringe Wassergehalt von Samen mit Veränderungen des Chromatins einhergehen, war bislang unklar. Das Team um Wim Soppe vom Max-Planck-Institut für Pflanzenzüchtungsforschung hat jetzt in Studien mit der Ackerschmalwand gezeigt, dass die Zellkerne während der Samenreifung deutlich schrumpfen und sich dabei auch das Chromatin zusammenknäult. Beide Prozesse kehren sich bei der Keimung um. „Die Größe des Zellkerns ist unabhängig vom Ruhezustand der Samen von Arabidopsis thaliana“, sagt Soppe. Vielmehr ist die Verkleinerung des Zellkerns ein aktiver Prozess, um die Resistenz gegenüber Trockenheit zu erhöhen. Die Kondensation des Chromatins wiederum erfolgt unabhängig von den Veränderungen des Zellkerns.

Durch die Erkenntnisse der Kölner Forscher könnten vielleicht auch andere Organismen vor Austrocknung geschützt werden. Denn die Mechanismen, die die Organisation des Chromatins regulieren, haben sich in der Evolution der Lebewesen kaum geändert.

Plant seeds protect their genetic material against dehydration

When seeds from the thale cress Arabidopsis thaliana mature, their cell nuclei reduce in size and the chromatin condenses

Plant seeds represent a special biological system: They remain in a dormant state with a significantly reduced metabolism and are thus able to withstand harsh environmental conditions for extended periods. The water content of maturing seeds is lower than ten percent. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research in Cologne have now discovered that the genetic material in seeds becomes more compact and the nuclei of the seed cells contract when the seeds begin to mature. The seeds probably protect their genetic material against dehydration in this way.

Plants prepare for changing environmental conditions in the best possible way by developing dormant seeds. Seeds that mature in autumn, for example, have no problem surviving the harsh conditions of winter. And when the seeds encounter more pleasant external conditions in spring, they germinate and reboot their metabolism, which has been running at a low speed. In archaeological excavations, seeds have even been found that had survived for several thousand years and were still able to germinate.

Dry seeds represent a transitional stage between embryonic and seedling stages. During developmental transitions, the genes that control the new state must be activated while the genes for the “old” stage are silenced. The genes in the cell nucleus are surrounded by proteins. This complex – the chromatin – can be tightly or loosely packed. The degree of compactness of the chromatin regulates the activity of the genes: the more “open” the chromatin, the better the genes can be read.

It was not known up to now whether the reduced metabolic activity or low water content of seeds was linked with changes in the chromatin. The research team working with Wim Soppe from the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research has now shown in studies on the thale cress that the cell nuclei clearly contract during seed maturation and the chromatin compacts as part of this process. Both processes are reversed during germination. “The size of the nucleus is independent of the state of dormancy of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds,” says Soppe. Instead, the reduction of the nucleus is an active process, the function of which is to increase resistance to dehydration. Again, the condensation of the chromatin arises independently of the changes in the nucleus.

Thanks to the discoveries of the Cologne-based researchers it may be possible to protect other organisms against dehydration, as the mechanisms that regulate the organisation of the chromatin have undergone little or no change over the course of evolution.