|

ETH Zürich chemists develop a new coating method to protect seeds from being eaten by insects - In doing so, they have drawn inspiration from the humble peach and a few of its peers

ETH-Chemiker entwickeln eine neue Beiz-Methode, um Saatgut vor gefrässigen Insekten zu schützen. Dazu kopierten sie das Abwehrsystem von Pfirsich und Co.

Zurich, Switzerland

May 23, 2016

A lesser grain borer on a wheat kernel: a new kind of coating could protect seeds from these beetles and their larvae. (Image: Clemson University - USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series, Bugwood.org)

Don’t eat the core, it’s poisonous: it's something parents often say to their children before they eat their first peach. Peach pits, which are hidden inside the nut-like husk, do in fact contain amygdalin, a substance which can degrade into hydrogen cyanide in the stomach.

But peaches, apricots and almonds didn’t develop this defence system to keep children from enjoying their fruit. It is actually nature’s way of protecting plant seeds from being eaten by insects.

Chemists from Wendelin Stark’s research group at ETH Zurich have drawn inspiration from this and copied the defence system of bitter almonds and other members of the Prunus family in the lab. They are developing a coating for seeds that functions in the same way as this natural model and is just as effective, but doesn’t impair seed germination and is also biodegradable. The study accompanying their work was recently published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Cyanide as a by-product of insect snacking

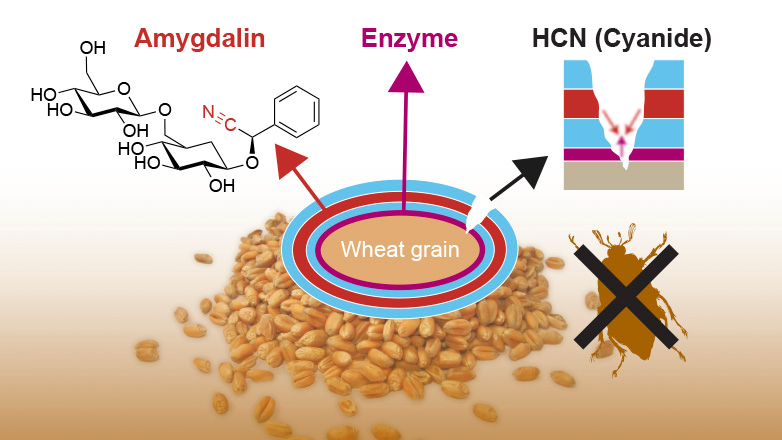

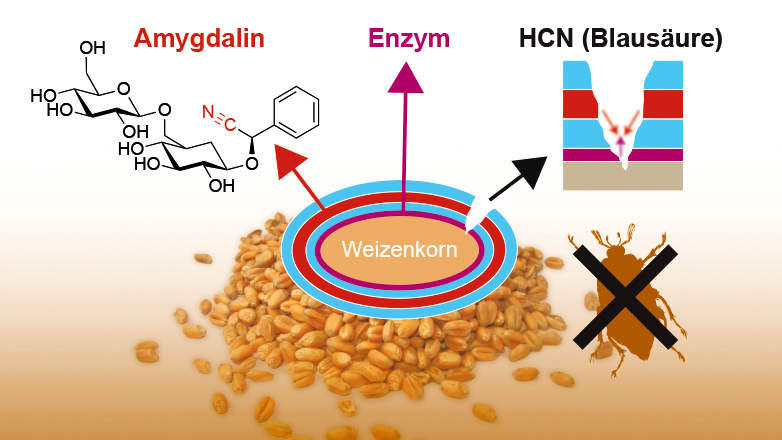

To determine the efficacy of a coating, the researchers tested different layer sequences. The sequence that finally emerged as the most effective consists of several layers of polylactic acid (PLA), a substance that is harmless to both humans and the environment. The innermost layer contains an enzyme. On top of this lies a layer of pure polylactic acid, followed by two layers in which the hydrogen cyanide precursor amygdalin is embedded – the same substance found in the husks of bitter almond seeds. A final layer is composed of pure PLA.

If an insect larva chews through these layers, the amygdalin is released, followed by the enzyme. The two substances mix together and the amygdalin breaks down into hydrogen cyanide, which kills the insect larva’s appetite – or even the creature itself.

Several layers of polylactic acid surround a wheat grain. An enzyme is embedded in the innermost layer, while the middle layers contain amygdalin. Insects can release these two substances as they feed, leading the enzyme to convert the amygdalin into hydrogen cyanide. This can weaken or kill the insect larvae. (Graphics: ETH Zurich)

Successful testing on insect pests

In collaboration with the Julius Kühn Institute in Berlin, the researchers have tested the efficacy of their treatment on a variety of cereal pests. The bitter almond defence system proved very effective against the larvae of the mealworm (Tenebrio molitor), the Indian mealmoth (Plodia interpunctella) and the lesser grain borer (Rhizopertha dominica). The lesser grain borer is a beetle that causes considerable damage to wheat stores worldwide.

Significantly fewer fully grown beetles hatched on coated than uncoated seeds. They reproduced less successfully and the larvae grew more slowly because they had eaten less.

However, the layering didn’t keep absolutely all insects from feasting on the wheat grains: the treatment was not effective against the wheat weevil (Sitophilus granarius). This type of beetle does not lay its eggs on the grain, but instead bores a hole into it for the eggs and seals it up afterwards. The larvae then eat the wheat grain from the inside out, which means that they don’t come into contact with the coating.

In addition, the researchers were able to show in laboratory and fieldwork that the treatment did not impair the germination of wheat grains. In the lab, 98% of the coated grains germinated. In the field, the coated grains did germinate a little later than the uncoated ones, and the seedlings initially developed more slowly. Nonetheless, the wheat plants were able to recover this initial deficit later on.

A possible replacement for pesticides

“We've demonstrated that this new kind of coating method works: the grains are protected from being eaten by insects and are usable in the field,” explain the study's authors Carlos Mora and Jonas Halter. The treatment using this method is as straightforward as it is with spraying. Nor are the costs of the new method significantly higher than with insecticides.

The ETH researchers are convinced that this kind of seed coating can be used on other kinds of crops too. “The method has the potential to replace certain synthetic pesticides,” believes Carlos Mora. “Not only is the coating biodegradable, but it also ensures that the seeds retain their quality in storage.”

References

Mora CA, Halter JG, Adler C, Hund A, Anders H, Yu K, Stark WJ. Application of the Prunus spp. Cyanide Seed Defense System onto Wheat: Reduced Insect Feeding and Field Growth Tests. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2016. DOI 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00438

Halter JG, Chen WD, Hild N, Mora CA, Stoessel PR, Koehler FM, Grass RN, Stark WJ. Induced cyanogenesis from hydroxynitrile lyase and mandelonitrile on wheat with polylactic acid multilayer-coating produces self-defending seeds. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2014, 2, 853-858. DOI: 10.1039/C3TA14249C

ETH-Chemiker entwickeln eine neue Beiz-Methode, um Saatgut vor gefrässigen Insekten zu schützen. Dazu kopierten sie das Abwehrsystem von Pfirsich und Co.

Den Kern nicht essen, der ist giftig: Das sagen Eltern ihren Kindern, ehe diese ihren ersten Pfirsich essen. Tatsächlich enthalten Pfirsichkerne, die sich in der nussartigen Schale verstecken, Amygdalin, eine Substanz, die im Magen in giftige Blausäure zerfällt.

Doch Pfirsiche, Aprikosen oder Mandeln haben dieses Abwehrsystem nicht dafür entwickelt, um Kindern den Früchtekonsum zu vergällen. Die Natur hat es hervorgebracht, um die Pflanzensamen vor gefrässigen Insekten zu schützen.

Chemiker aus der Forschungsgruppe von Wendelin Stark an der ETH Zürich haben sich nun davon inspirieren lassen und das Abwehrsystem von Bittermandeln und Konsorten im Labor kopiert. Sie entwickelten für Saatgut eine Beizung, die genauso wirksam ist und ähnlich funktioniert wie das natürliche Vorbild, die Keimung der Samen jedoch nicht beeinträchtigt. Darüber hinaus ist die Beizung biologisch abbaubar. Die entsprechende wissenschaftliche Publikation erschien soeben in der Fachzeitschrift «Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry».

Beim Knabbern entsteht Blausäure

Um die wirksamste Beize zu bestimmen, testeten die Forscher verschiedene Schichtfolgen. Am Ende entpuppte sich folgende Abfolge als die wirksamste: Sie besteht aus mehreren Schichten Polymilchsäure (Polylactat, PLA), eine für Mensch und Umwelt harmlose Substanz. Die innerste Schicht enthält ein Enzym. Darüber liegt eine Schicht aus reiner Polymilchsäure, darüber zwei Schichten, in denen die Blausäure-Vorläufersubstanz Amygdalin eingebettet ist – die gleiche Substanz, die auch in der Schale von Bittermandel-Samen steckt. Den Abschluss macht eine weitere Schicht reiner PLA.

Mehrere Schichten Polylactat umgeben ein Weizenkorn. In der innersten Schicht ist ein Enzym eingebettet. Die mittleren Schichten enthalten Amygdalin. Setzt ein fressendes Insekt die Substanzen frei, baut das Enzym Amygdalin zu Blausäure ab. Diese schwächt oder tötet die Insektenlarven. (Grafik: ETH Zürich)

Frisst sich nun eine Insektenlarve durch diese Schichten hindurch, setzt sie erst das Amygdalin frei, dann das Enzym. Die beiden Substanzen vermischen sich, das Enzym baut Amygdalin zu Blausäure (Cyanid) ab. Diese verdirbt der Insektenlarve den Appetit – oder tötet sie.

Test an Schadinsekten erfolgreich

Die Forschenden haben in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Julius Kühn Institut in Berlin die Wirkung ihrer Beizung an mehreren Getreideschädlingen getestet. Gegen Larven des Mehlkäfers (Tenebrio molitor), der Dörrobstmotte (Plodia interpunctella) und des Getreidekapuziners (Rhizopertha dominica) wirkte das Bittermandel-Abwehrsystem sehr gut. Der Getreidekapuziner ist ein Käfer, der weltweit in Weizenspeichern grosse Schäden anrichtet.

Auf gebeiztem Saatgut schlüpften deutlich weniger erwachsene Käfer und Motten als auf unbehandeltem. Sie vermehrten sich weniger stark, auch wuchsen die Larven langsamer, weil sie weniger frassen.

Die Beschichtung hielt jedoch nicht alle Schadinsekten davon ab, an den Weizenkörnern zu knabbern: Gegen den Getreiderüssler (Sitophilus granarius) wirkte diese Beizung nicht. Diese Art von Käfer legt seine Eier nicht auf die Körner, sondern bohrt sie in diese hinein und verschliesst das Bohrloch. Die Larven fressen das Weizenkorn dann von innen her auf. Dadurch kommen sie nicht mit der Beizung in Kontakt.

Die Forscher konnten überdies mit Labor- und Feldversuchen zeigen, dass die Beize die Keimung der Weizenkörner nicht störte. Im Labor keimten 98 Prozent der behandelten Körner. Auf dem Acker keimten diese zwar etwas später als unbehandelte, und die Keimlinge entwickelten sich zu Beginn des Wachstums langsamer. Dieses anfängliche Defizit konnten die Weizenpflänzchen später jedoch aufholen.

Möglicher Ersatz für Pestizide

«Wir haben aufgezeigt, dass diese neuartige Beizmethode funktioniert: Sie schützt die Körner vor Insektenfrass, und die Körner sind auf dem Acker brauchbar», sagen die Autoren der Studie, Carlos Mora und Jonas Halter. Die Beizung mit dieser Methode sei vom Verfahren her so einfach wie die mit Spritzmitteln. Auch überstiegen die Kosten der neuen Methode die von Insektiziden nicht wesentlich.

Die ETH-Forscher sind davon überzeugt, dass diese Art des Beizens auf das Saatgut anderer Nutzpflanzen übertragen werden kann. «Die Methode hat das Potenzial dazu, gewisse synthetische Pestizide zu ersetzen», meint Carlos Mora. «Die Beize ist nicht nur komplett biologisch abbaubar, sie sichert auch die Qualität des Saatguts bei der Lagerung.»

Literaturhinweise

Mora CA, Halter JG, Adler C, Hund A, Anders H, Yu K, Stark WJ. Application of the Prunus spp. Cyanide Seed Defense System onto Wheat: Reduced Insect Feeding and Field Growth Tests. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2016. DOI 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00438

Halter JG, Chen WD, Hild N, Mora CA, Stoessel PR, Koehler FM, Grass RN, Stark WJ. Induced cyanogenesis from hydroxynitrile lyase and mandelonitrile on wheat with polylactic acid multilayer-coating produces self-defending seeds. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2014, 2, 853-858. DOI: 10.1039/C3TA14249C

More news from: ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich)

Website: http://www.ethz.ch Published: May 23, 2016 |